On allegiance, awakening, and a Kingdom that has no flag.

I can’t remember a time when I haven’t known and said the Pledge of Allegiance. I learned it before I could spell half the words in the pledge — hand on heart, eyes on the flag, voice in unison with every other child in the room. I’ve said it thousands of times since learning it, at assemblies, graduations, and civic events.

I’ve always loved this country. I’ve seen enough of the world to know what a rare and fragile thing our experiment in democracy is. I’ve lived and worked in places where freedom is not a given — where poverty, corruption, and instability weigh heavily — and I’ve met people who look to the United States as a symbol of hope. For all our flaws and the divisions we are currently living through, I still believe there is something remarkable about the ideals we profess: liberty and justice for all.

And then one morning, somewhere between prayer and pledge, I realized I couldn’t say the words anymore. It wasn’t anger. It wasn’t rebellion. It was just… clarity. The recognition that the words on my lips no longer matched the allegiance of my heart.

A Small but Honest Change

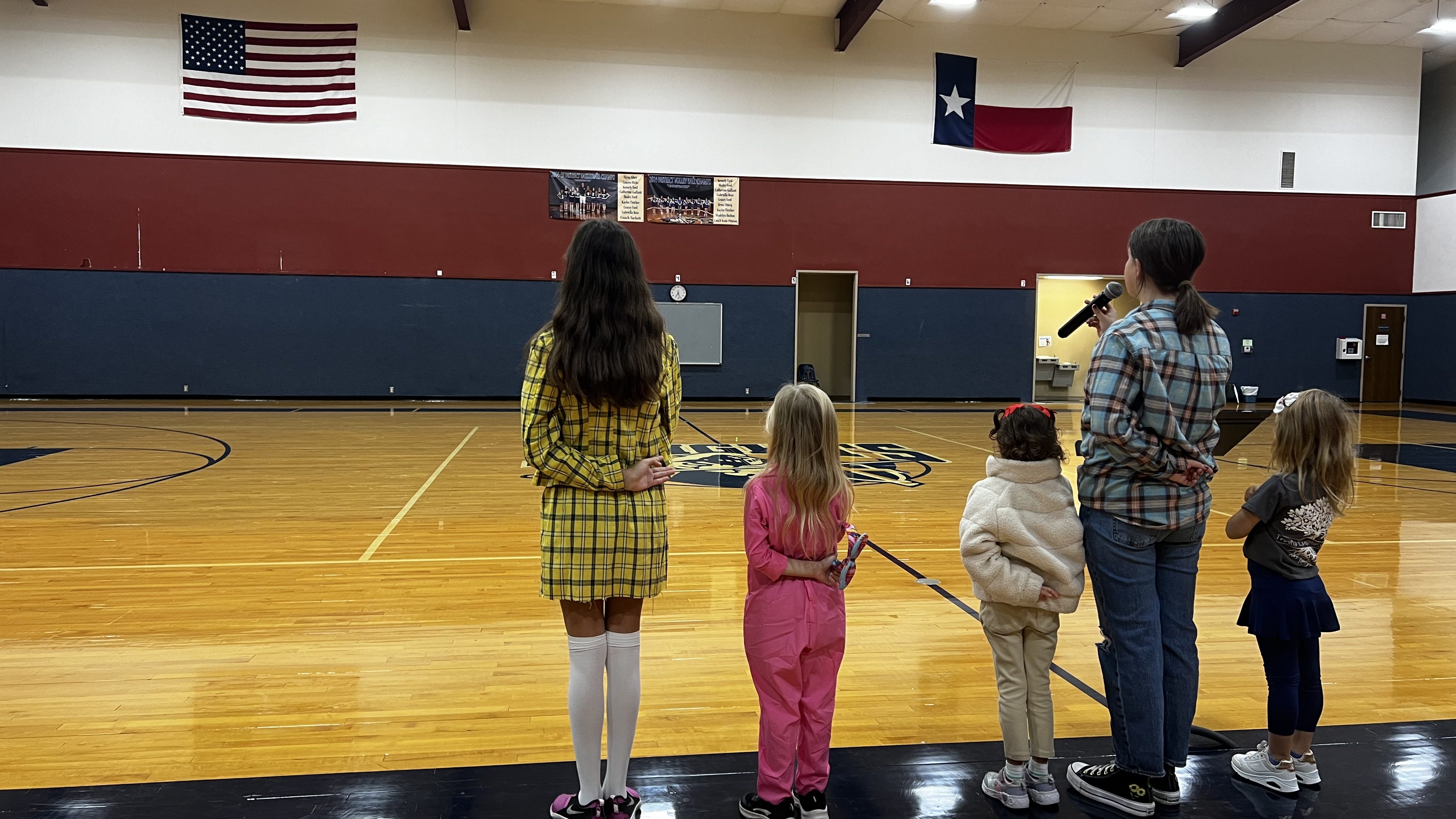

I am the chaplain of a parish school but am only on their campus once or twice a week. When I am, it’s usually for morning prayer (Eucharist is just once a month). Together we pray to the God who made us, redeemed us, and calls us to love our neighbors as ourselves. We proclaim Jesus as Lord and commit our hearts and minds to God’s work in the world. And then — without missing a beat — we turn to the flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance.

And after the national pledge, we turn to the other enormous flag in the room and pledge to that one too — to the Texas flag.

“Honor the Texas flag; I pledge allegiance to thee, Texas, one state under God, one and indivisible.”

I can’t even bring myself to whisper those words anymore. The language feels heavier now, as our state sends troops across state borders and defines “neighbor” more narrowly by the day. It’s one thing to honor the place you come from; it’s another to pledge your allegiance to it.

Don’t get me wrong. I will still stand. Out of respect for my students and colleagues, and for the freedoms this country represents, and because I refuse to give up hope that we might one day truly stand for liberty and justice for all. I will stand. But I will no longer speak the words. I will no longer place my hand over my heart.

It’s not defiance. It’s devotion.

Every time I move from “Jesus is Lord” to “I pledge allegiance,” I feel the dissonance in my chest. I can’t offer two ultimate loyalties. One of them — the first one, the only one, the one that matters — belongs to God.

As Jesus said, “No one can serve two masters.” (Matthew 6:24)

And as the apostles told the authorities, “We must obey God rather than human beings.” (Acts 5:29)

Those words aren’t about disrespect or rebellion. They’re about rightly ordered love — what Augustine called the “order of affections.” Patriotism has its place. But worship does not belong to any nation, flag, or political ideal. My heart already has a King.

The Pledge as a Morning Liturgy

The pledge was written in 1892 by Francis Bellamy, a Baptist pastor and Christian socialist who hoped to inspire unity and civic pride after the Civil War. His original version made no mention of God — that came later, in 1954, when Congress added the words “under God” during the Cold War to distinguish America from communists and atheists. What began as a civic statement slowly took on the tone of a creed.

By the middle of the twentieth century, the pledge had become a daily fixture in public schools. Civic groups promoted it as a way to instill patriotism, and soon generations of children began their day with hand on heart, reciting the same words before they even knew what they meant.

It was meant to unify us. But like any liturgy, repetition does more than remind — it forms. Over time, the pledge became part of our spiritual muscle memory. We said it automatically, the way we once said bedtime prayers or Sunday creeds before we had language for what we believed.

And as with inherited faith, there comes a moment of reckoning — a time when we’re called to examine what we’ve been taught and decide what still holds true. For me, that reckoning came somewhere between prayer and pledge, when I realized that what once felt like civic virtue now asked for something my faith could no longer give.

The Blurring of Worship and Patriotism

When I first came to my school, I learned that my predecessor had to rewrite the liturgy for morning prayer because the pledges had been placed inside the service itself. Imagine that: a civic oath inserted into a Christian act of worship. It’s such a small detail, but it reveals how easily civil religion seeps in — how quickly we stop noticing when patriotism starts borrowing the posture of prayer.

That’s where my discomfort lives.

I love this country. I give thanks for the freedoms I enjoy and for the countless people who have sacrificed to preserve them. But when I pledge allegiance, hand over heart, right after praying to God, something in me feels out of place, off kilter. The words ring hollow — or worse, divided.

Scripture speaks often about divided hearts. “You shall have no other gods before me,” says the first commandment (Exodus 20:3). “Set your minds on things above, not on things on earth,” writes Paul (Colossians 3:2). “Our citizenship is in heaven,” he reminds the Philippians (3:20).

Those aren’t calls to abandon the world. They are calls to remember where our truest allegiance lies.

From Patriotism to Christian Nationalism

Over the past few decades, that blending of faith and nation has helped something larger and more dangerous take root: Christian nationalism — the idea that America has a special covenant with God, that Christianity and patriotism are one and the same, and that to question either is to betray both.

It’s an idea that dresses empire in religious clothing. It turns discipleship into ideology. It takes the language of faith — blessing, chosen, redeemed — and applies it to a nation instead of to people made in God’s image.

When we teach children to say “one nation under God” without teaching them what it means to live under God’s justice, mercy, and humility, we’ve traded formation for familiarity.

Standing in Silence

So from now on, I’ll stand — respectfully, quietly, prayerfully — but I won’t speak.

I won’t do it to make a scene or start a debate. I won’t tell anyone else what they should do. I won’t even mention it in school. This isn’t about me modeling something for the students (although I’m not against that). This is simply where my conscience has led me.

My allegiance — my true, eternal allegiance — is already spoken for.

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.” (Matthew 22:37)

I will keep loving this country. I will keep praying for its leaders, its people, its healing. But I cannot pledge to it. Because I’ve already pledged myself — body and soul — to a kingdom that has no flag.

For me, silence while others are pledging will become its own kind of prayer — a reminder that love of country and loyalty to God are not the same thing, and that only one deserves my pledge.

~ Rev. Dana